You are in:

Laureates

Start of main content

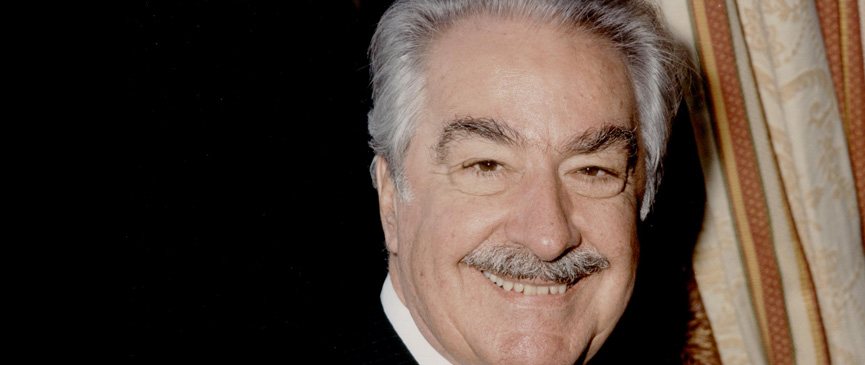

Álvaro Mutis

Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 1997

Majesty,

Highness,

Distinguished authorities,

Distinguished Sirs,

Ladies and gentlemen,

The immense satisfaction and warm gratitude that I feel today upon receiving the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature goes far beyond the explainable pleasure of having my literary work receive similar recognition. It so happens that this Award stirs up older and deeper feelings than that of the simple vanity of a writer, and these have their origin in two areas that mutually compliment and enrich each other. The first one is constituted by the presence of Spain in the family tradition and the second arises from my condition as an Ibero-American.

At the risk of falling, without recourse, into the anecdotal and personal, I wanted to say something about a tradition that we Mutises in Colombia have known how to perpetuate with unshakable fidelity. It has to do with what I would call a watchful and unfailing interest in Spain, handed down from one generation to the next, resembling something very much like a family trait. Without question, the origin of this attitude is to be found in the tutelary presence of the learned naturalist, the canonical José Celestino Mutis, artificer of the Botanical Expedition of New Granada, to which he was commissioned by H.M. the King Carlos III. José Celestino brought his brother Manuel from Cádiz to help him with the arduous scientific task that would take him three decades to bring to a happy conclusion. Manuel Mutis y Bosio, father of my great-great-grandfather, raised a family in Colombia that has been bound up with the history of the country in the most diverse fields and occupations. The memory of the learned Mutis has flown through the lives of my family in a parallel way to the presence of Spain and its destiny. Of the many anecdotes that attest to this, I wanted to call on one in which I was a direct participant. When the sight of my paternal grandmother no longer allowed her to read the newspaper, I, as a child, read it aloud to her. She always began each occasion by saying: "Look, before anything else, at what they tell us about Spain". It was thus that, at the same time, I began to frequent the family library for the Spanish authors and I indulged in the reading of Galdós, Pereda, Juan Valera, Palacio Valdés and, in my estimation, the unjustly forgotten Navarro Villoslada, with his "Amaya and the Basques in the 8th Century", which left a rather dizzying imprint on my childhood dreams. Coming later there would be, unmistakably and now for my own sake, such timeless classics as Jorge Manrique, Garcilaso, Miguel de Cervantes, Tirso, and with them the authors from the Generation of '98, and in particular, at the top of my literary passions until the present day, Antonio Machado.

Today Spain overwhelms me with an honor, but not for having merited less than one possessed of a very deep significance. The Prince of Asturias Award for Literature revives all of these family remembrances and brings them into the present, providing me with a well-being and an assurance that I had taken for lost in the midst of my itinerant and uncertain destiny. It is as if I were listening to the voice of this venerable land speaking to me: "I have followed all of your steps, listened to your voice, and today I receive you as another son born in those lands of America that are so dear to me". I cannot find a better way, albeit somewhat sentimental and tinged with candor, to explain how I feel today in these surroundings and in the presence of such eminent persons who have always commanded my respect.

The other area in which the Award begins to awaken feelings in a way as stimulating as it is inevitable originates from my condition as an Ibero-American.

The most intense and definitive image of my Latin America lies in the equatorial zone and, more concretely, in an area which we are wont to call Tierra Caliente, the ideal climate for sowing coffee, sugar cane, and cacao; that place of torrential rivers which rush down the Cordillera and immense trees in permanent bloom. An area entirely different from the tropics, with which it is likely to be confused in other latitudes. There I had the pleasure and fortune of experiencing Paradise on earth: the plantation of my maternal family, steeped in these traditions of the soil. In this place, where I spent long periods as an ineffectual student and insatiable reader, my literary vocation was born. There is not one single line in my poetry or in my stories which does not have its secret root in this region that I guard in my memory in order to help me continue living. I write only to keep this remembrance intact and to give it a chance at fleeting posterity through the work of my potential readers. Yet it is necessary to admit that I am talking about a Paradise whose existence has faded away, razed by this infernal devourer which has been given the name of modernity. Not a single trace is left for me of this sacred spot, and the fact that today I am receiving, here, by virtue of my work, a homage to which, coming from where it comes from, I grant a value of indescribable transcendence. I now wanted to comment on the most evident causes as to why this corner of my America is today a barren ruin without a soul.

No one can escape from the fact that we are bystanders to the vertiginous death throes of all the principles and convictions that have marked out, during millennia, the behavior of man, whose profile as a person is steadily being effaced and replaced by the phantasm that strives to imitate it on the hazy electronic screen. It is thus that these new means of alleged communication, put at the disposal of a consumer society, becoming vaster and more desolate with every passing day, conspire to annul the notion of the individual and the very existence of the person that already matters next to nothing and is going to be dissolved into that amorphous mass that moves to the impulse of a raw hedonism and a Cain-like angst that invades every region of the planet with increasing frenzy. How utterly right, on that occasion, was he who sounded his voice in alarm in this very same hall and in identical circumstances: "We're walled in!", he said. Indeed we are, and it is time that we became aware of it and looked for the remedy in the secret codes that have marked our destiny for millennia. Where are they to be found? The answer is evident: they are in the ruins of Tartesos; in the rugged vestiges of Rome over the entire length and width of the peninsula; in the lesson left to us by the Omayyads, translators of Plato and Aristotle; in the luminous esoteric vision of the Celts and Iberians and, last but not least, in the wisdom of the Mayas, Toltecs, Incas, and the other Pre-Colombian civilizations of America. In the aggregate of each and every one of these fecund legacies, from one side of the ocean to the other is, I am certain, the resource for surmounting the encirclement and checking the deadly overtures of globalization and the blind surrender to mechanical means that make an attempt against being to the point of immolating it into obscurity.

We, Spaniards and Ibero-Americans, are still the owners of a mythic conscience destined to preserve our condition as individuals. This redeeming voice has revealing echoes in ceremonies like the one that we are present at today, where Spain generously acknowledges the diverse fields of human achievement, represented here by persons of varied origin and condition, on whose behalf I have the honor of speaking. We conceive of this ceremony as a rite which enables us to drive away the impending onslaught.

I invite you to listen to the lucid and prophetic warning given to us by a great poet of today's Spain, Julio Martínez Mesanza, in his poem "Exaltation of the Rite". It reads thus:

Whoever does not understand the reason of the rite,

whoever does not understand majesty and gesture,

never will know the human heights,

his vain god will be contingency.

Whoever debases the forms and then delivers

neutral simulacra to the people

in order to earn fame as a free man,

has neither god nor country nor destiny.

Thank you very much.

End of main content

Sección de utilidades

Fin de la sección de utilidades

- Legal document Legal document (Access key 8)

- | Privacy policy Privacy policy (Access key )

- | Social networks ???en.portal.pie.menu107.title???

- | Cookies ???en.portal.pie.menu110.title???

- | Site map Site Map (Access key 3)

- | Contact Contact (Access key )

- | XHTML 1.0

- | CSS 2.1

- | WAI 'AA

© Copyright 2024. FUNDACIÓN PRINCESA DE ASTURIAS