You are in:

Laureates

Start of main content

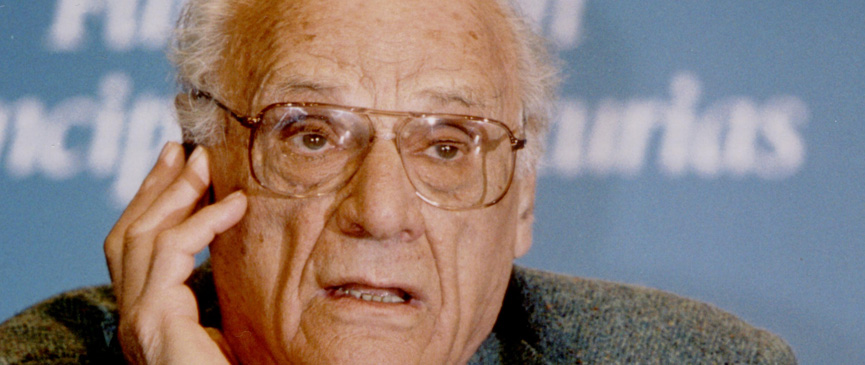

Arthur Miller

Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 2002

The awarding of this great prize to my work turns memory to my connections with Spain and her culture. I have never lived here or spent more than a few weeks at a time in several visits with my late wife, Inge Morath, over the years, but from my youth Spain has had some especially significant, even dramatic affects on my consciousness.

I had just entered my twenties when the Civil War broke out with the revolt led by Franco against the Republic. There was no single event as powerful in the formation of my generation's awareness of the world. To many it was our initiation into the Twentieth Century, probably the worst century in history. The Spanish agony has turned out to be classic, the model for many other democratic governments' overthrow by military forces espousing a return to Christian values. Two of my university classmates went off to fight with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, one of them, Ralph Neaphus, never to return. For nearly four years the first news we looked for in the morning papers was the news from the Spanish front.

The word "Spain" in the Thirties was explosive, the very emblem of resistance not only to the forced return of clerical Feudalism in the world but to the rule of unreason and the death of the mind. For many, even then, the Civil War, with the Nazis and Mussolini's troops in open support of Franco, was the opening battle of the Second World War.

"Spain" also meant Picasso and his "Guernica" painting. Yes, it was still hard to believe that an airforce pilot, even of the Nazi air force, could fly low over an open sunlit square and drop bombs on civilians. As time went on "Spain" would exemplify the struggles of many other peoples to emerge into modernity from the fog and futility of tenacious feudal institutions. "Spain" would often be brought to mind in China in its struggle to rid itself of feudal habits and ways of thinking. "Spain" came tragically to mind in Chile where Pinochet had overthrown another elected government.

In more recent years Inge Morath would open up quite another Spain to me, the Spain she had come to love, the country where I think she felt most at home. This was the country of great painters and of her friend Balenciaga but also of peasants and townspeople and bullfighters whom she loved to photograph. She saw in the Spanish character a certain aspiration for nobility which I think reflected her own. Starting in the early Fifties, when Spain attracted little interest from the world's culture, she photographed through the half century, and with a manifest love and respect for the soul of the people which was her real subject. Alongside her absolute mastery of the Spanish language and customs and history I could do little more than look on in wonder.

Our Spanish experience all came to a climax about a year and a half ago, when I accompanied her on a visit to the town of Navalcan. A show of her pictures was on in Madrid at the time and among them a group of images which she had taken in the Fifties in what was then a remote, rarely visited village. Now, fifty years later word had gotten back to Navalcan that the place had achieved reknown. A busload of villagers went to Madrid to see themselves as they had looked so long ago. They stood in the gallery, middle-aged now, survivors seeing themselves young and full of energy at their birthday parties, weddings, in their fields and homes, surrounded with friends now grown old or passed away. They returned to Navalcan and got word to Inge insisting that she must come back for a visit.

We were travelling with our friend Derek Walcott, Nobel-prized poet and an experienced man of the world. Certainly more than a thousand people had come out into the streets to greet and celebrate Inge on her return. The fire and police departments sent representatives and a lunch in the town hall was laid for sixty. Walcott stood with us in the midst of this crowd which kept showering Inge with corsages, pressing glasses of wine upon her, babies to kiss, while calling out their memories of her last visit half a century ago. It was simply that she had once recognized them and had given their obscure lives a record and a public memorial. The love in their faces was palpable. I happened to look over to Walcott and saw tears in his eyes. "I've never in my life seen anything so beautiful", he said. The climax of the visit was the presentation to Inge by the mayor of a new street sign reading "Calle Inge Morath". They were going to rename a street in her honour.

So I do not come empty-handed to you and to the modern and democratic Spain but with memories of my own, some tragic, some happy. In that spirit I wish to thank you for your recognition and this great award.

End of main content

Sección de utilidades

Fin de la sección de utilidades

- Legal document Legal document (Access key 8)

- | Privacy policy Privacy policy (Access key )

- | Social networks ???en.portal.pie.menu107.title???

- | Cookies ???en.portal.pie.menu110.title???

- | Site map Site Map (Access key 3)

- | Contact Contact (Access key )

- | XHTML 1.0

- | CSS 2.1

- | WAI 'AA

© Copyright 2024. FUNDACIÓN PRINCESA DE ASTURIAS

Speech by the laureate

Speech by the laureate