Main content

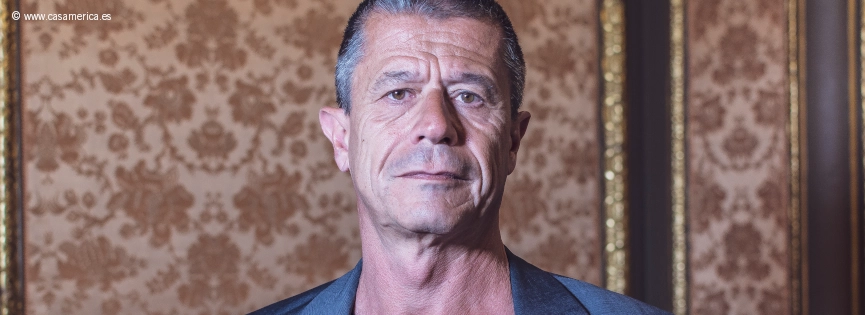

Emmanuel Carrère 2021 Princess of Asturias Award for Literature

Your Majesties,

Your Highnesses,

Members of the Foundation,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Friends,

Granting me this Award constitutes a great honour, all the greater because it is a Spanish honour.

I would like to speak and read in Spanish, but unfortunately I neither speak nor read the language. However, I just took a look at my library, which is classified by language. It is a classification like any other; we all know that none is totally satisfactory. By alphabetical order, genre, century, publisher, affinities... whatever? By language has its advantages. In any case, I noticed that in the top three on the list of books on the shelves, Spanish comes right behind English and ahead of Russian. Approaching those shelves is to say hello to old friends. A grandfather younger than all the young folk: Cervantes. Two ironic and enigmatic uncles: Borges and Bioy Casares. Cortázar, in whose building I lived for ten years, on a street in the 10th district of Paris, once a working-class neighbourhood that has nowadays become gentrified. Roberto Bolaño, the elder brother everyone dreams of, adventurous and charming like Robert Louis Stevenson must have been. And also some fellow travellers, more or less my age: Enrique Vila-Matas, Javier Cercas, Juan Gabriel Vásquez... And my dear cousin Rosa Montero.

I wish to express my gratitude to the authors who forged me, but also to the publishers who have published my work. The fact that my books have little by little managed to win over readers in Spain, that I appear before you here this evening, is largely thanks to the patient and faithful work of Anagrama. Of Anagrama, which is to say, of our great and beloved Jorge Herralde, and to say Herralde is also to say Lali Gubern, and to say Anagrama today is also to say Silvia Sesé. And it is also thanks to the faithful and subtle work of Jaime Zulaika, who has been my translator for many years now.

There is a cruel absence here this evening. That of Paul Otchakovsky- Laurens, my friend and French publisher for thirty-five years, who died three years ago. No one can replace him, but Emmelene Landon is here, who is not only his widow, but also a wonderful painter and writer, as well as my best friend. The POL publishing house carries on and does so admirably headed by Jean-Paul Hirsch, who has kindly attended this event together with his wife Jacinthe, as has François Samuelson, my long-time agent. My thanks to all three of them. Finally, I would like to thank Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet, for being the woman she is, for directing the films she directs, for sharing life with me.

There you have it.

I wrote this short speech believing that I had, as they say, ‘gone through the motions’, and I sent it to the Princess of Asturias Foundation to be translated in time for the ceremony. A few days later I received an email from the Foundation that was a masterpiece of tact. They told me that my brief speech was wonderful, absolutely wonderful, and my list of thanks totally justified, totally in keeping with a similar circumstance, but that precisely in the present circumstance, how to phrase it, somewhat more was expected of me, something –and I cite the English term used– slightly more ‘inspirational’. I don’t know what the exact interpretation of this adjective would be: slightly more inspiring, slightly more inspired, a little of both. In any case, what was to be inferred from this tremendously tactful message is that, believing that I had done the appropriate thing, in the same way that one follows dress code, I had written a suitable, one might even say conventional speech, a reproach that I sincerely have not often received.

I did not wish to relinquish my list of thanks because the people I have thanked are really dear to me, but I have tried to round it off with something slightly more inspiring, and I have not needed to cast my gaze very far. I have not needed to search very far because at this very moment I am dealing with something extremely, one might even say, tragically inspiring about which I would like to say a few words.

On 8th September last, the trial began in Paris for the attacks on the street cafés and in the Bataclan concert hall that also took place in Paris, on 13th November 2015. Those attacks resulted in 131 deaths. You Spaniards had cause to weep even more on 11th March 2004, when there were 61 more deaths, if this atrocious accounting makes any sense at all. For us, they were the most lethal attacks ever perpetrated on French soil. The murderers were killed or blew themselves up. The fourteen scoundrels in the dock are what in French we call seconds couteaux, secondary figures, which invalidates the comparison that is often made with the Nuremberg trials, where very high-ranking Nazi dignitaries were tried. But what the Paris trial has in common with the Nuremberg trials is its historical ambition, its enormous resources and, first and foremost, its duration: nine months. I decided to follow this trial in its entirety. From start to finish, every day. Something interesting does not happen every day, of course, but it is impossible to know in advance whether it will or not. Sometimes sessions that everyone expects to be exciting are extremely boring, while others, of which nothing was expected, are exciting, such as the testimony of forensic doctors and ballistics experts. It is a maxim that all court journalists are familiar with and that has practically no exception: if you are not there, something will happen. Therefore, Your Majesties, Your Highnesses, dear friends, however great the honour of being here tonight may be for me, A part of me continues in the Paris courtroom.

Everyone who has followed a major trial knows that it is one of the most addictive experiences to be found. What this trial seeks to do is inordinate: it aspires to reveal everything that happened during those terrible hours from all angles, from the point of view of all those involved, going back as far as possible in the genealogy of events. The Anatomy of a Moment, to quote the title of Javier Cercas’ forceful chronicle. This trial is also extraordinarily testing. Day after day we wade through blood, in physical and moral wounds, heinous deaths, and lives cut short. It is a blood bath of horror and we sometimes wonder why we inflict it on ourselves.

We inflict it on ourselves because it is not just a blood bath of horror. Because the testimonies that are given week after week, at the rate of around fifteen per day, are often extraordinary examples of humanity. Those survivors wounded in body and soul are still standing. They speak to us from far off, from places of human experience that most of us do not know. “Man,” wrote Léon Bloy, “has places in his poor heart that do not yet exist, and into them enters suffering, in order that they may have existence.” This trial also serves this purpose: to collectively explore these confines of our heart.

Throughout these testimonies, we discover something else surprising. Stories of shipwrecks, of catastrophes, of the generalization of ‘every man for himself’ usually reveal the worst in human beings. Cowardice, the law of the jungle, cannibalism. There is none of that here. It is impossible to imagine that a collective fiction of nobility and greatness of mind has been constructed, and yet we have practically heard nothing but acts of mutual help, solidarity, gestures that are often heroic. Many blame themselves for trampling others while trying to flee; none of those trodden underfoot reproaches others for doing so. Everyone tried to protect the man or woman they loved, but some did something else: they risked their lives to protect strangers. It is a mystery that at times converts what is abominable into infinite exaltation.

I will end this speech, which has now become too long, with two quotes.

The first is from Simone Weil,

“Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvellous, intoxicating. Therefore ‘imaginative literature’ is either boring or immoral (or a mixture of both). It only escapes from this alternative if in some way it passes over to the side of reality through the power of art, and only genius can do that.”

The second is from a Bataclan survivor,

“A few days after the attack my father died, and just before he died he told me, ‘You and I console others for the misfortunes that happen to us.’ I would have preferred not to have to console you.”

Merci Votre Majesté,

Merci Vos Altesses,

Merci Mes chers amis.

Translated by Paul Barnes

End of main content